Hurricanes Helene and Milton in the Southern United States, flood Dana in Spain, flash floods in Nova Scotia, cyclones in the Philippines, and droughts in Zambia and Zimbabwe were only some of the catastrophic weather events that occurred in just October and the first two weeks of November 2024. At the start of 2025, California was met with the unfortunately familiar sign of wildfires, which took the life of at least 29 people. After the COVID-19 pandemic exploded into global concern during the early months of 2020, most people became familiar with the phrase “unprecedented times”. A phrase that, today, is often repeated when catastrophes such as these arise. In reality, the circumstances that have allowed for these disasters to happen are not only precedent but also forewarned.

For one, zoonotic diseases like coronavirus are directly linked to climate change. Fluctuating temperatures, habitat loss, and a subsequent increase in human-animal contact allow for pathogens to live longer and be transmitted more easily. With the “bird flu” dominating headlines, the evolution of diseases caused from increased interspecies contact is once again relevant.

Hurricane Irma made landfall in 2018, breaking meteorological-based records for tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin, and since then, each tropical cyclone seems to be the worst one yet. Less than a month apart, Hurricanes Helene and Milton collectively hit Mexico, Cuba, the Bahamas, and four states in the United States, killing nearly 300 people, and leaving millions without electricity if even a home. While hurricanes are something that Floridians have long been familiar with, the frequency and severity of them are not. “My mom was born here in 1976,” said Genevieve Anderson, a freshman at Cypress Lake High School. “Her first hurricane was in 2004, but since Irma, she’s experienced three hurricanes in the past six years.” Like many of her classmates, Anderson knows the frequency of these cyclones is an indicator of something greater and is afraid of what devastation might happen if change doesn’t.

Following flood Dana, people throughout all regions of Spain banded together, rallying their efforts to help those most affected in Valencia, where over 227 people lost their lives to the flood. “Here is your crystal generation” was the title of many videos that showed people – predominantly young people – working in Valencia shoveling mud, distributing food, and cleaning houses. In their usual fashion, Gen Z used social media as a way of diffusing information, with TikToks explaining how to get to the affected areas, how to help, and even “Get Ready With Me” videos that explain the necessary safety precautions that need to be taken when working in these areas. The title “crystal generation” came as a direct reference to a belief held by the older generation in Spain, who claim that Gen Z are too sensitive to survive in the real world, and break easily.

This nickname is among many things that make young people in Spain feel as if the older generations, and their government, doesn’t respect them or take their concern seriously, a sentiment that is often shared by Gen Z worldwide. While the goal following Dana was to help its victims, it became an opportunity for this underestimated demographic to show how resilient they truly are and that they should be taken seriously. The togetherness and community that were created in the moment of crisis seemed to have an impact on the social perspectives within the country, but it didn’t solve the overarching problem.

Will people only listen to warnings after they become obsolete? How much destruction must the world experience before young voices are held in the regard necessary to guarantee they will have a world to grow up in?

Some would argue that these catastrophes were inevitable, that nature is something beyond human control and natural disasters are just that. But this would ignore the fact that connects these catastrophes, a fact that millions of young people are aware of and beg older generations to take seriously: that climate change is accelerating and worsening natural disasters, that action needs to be taken immediately, and that every day the changes that are being caused become more irreversible.

Teens and children draw attention to themselves when they speak out because they are so young, a double-edged sword that also leads them to be told to take a step back and listen, to research and learn and come back when they are older. Greta Thunberg was sixteen when she was invited to speak at the UN Climate Summit, where she begged world leaders to do something other than talk about profit margins and pass problems on to the next generations. She has been scolded and ridiculed by leaders worldwide, with then former-president Donald Trump tweeting that she must “work on her Anger Management problem.”

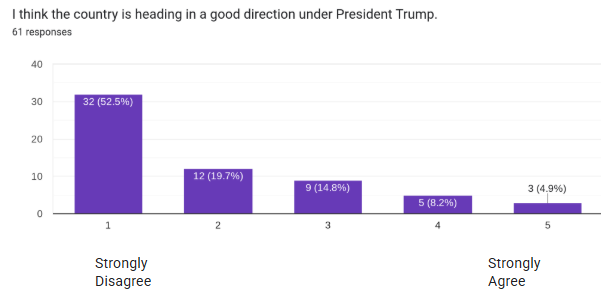

President Donald Trump was sworn into office for his second term a month ago, when he signed an executive order to once again withdraw the United States from the Paris climate agreement, mirroring his 2017 decision which had been reversed by former president Joe Biden in 2021. This decision has caused great concern all over the world, given that the United States has consistently been the country with the second-largest carbon dioxide emissions, contributing a whooping 12.6% in 2022. As if that wasn’t enough, Trump has called to “Drill, baby, drill” for oil in Alaska. A promise of environmental destruction, irreversible damage, and money.

A call to action seems like little more than a tantrum when lawmakers and general populations alike are aware of the reality our planet is facing. The majority of people across all levels of education and the world have been told about the Amazon forest, the Great Barrier Reef, and the climate clock. Schools and politicians alike tell kids that it’s up to them to solve the climate crisis. What use does it have, handing eight-year-olds a doomsday clock, when no one will hear them out about its ticking for another decade, if at all?

The actions that are being taken and the disasters they will lead to are as predictable as they are avoidable. The only uncertainty that remains is whether or not the cries for change will become louder than the sound of the printing of money before it’s too late.